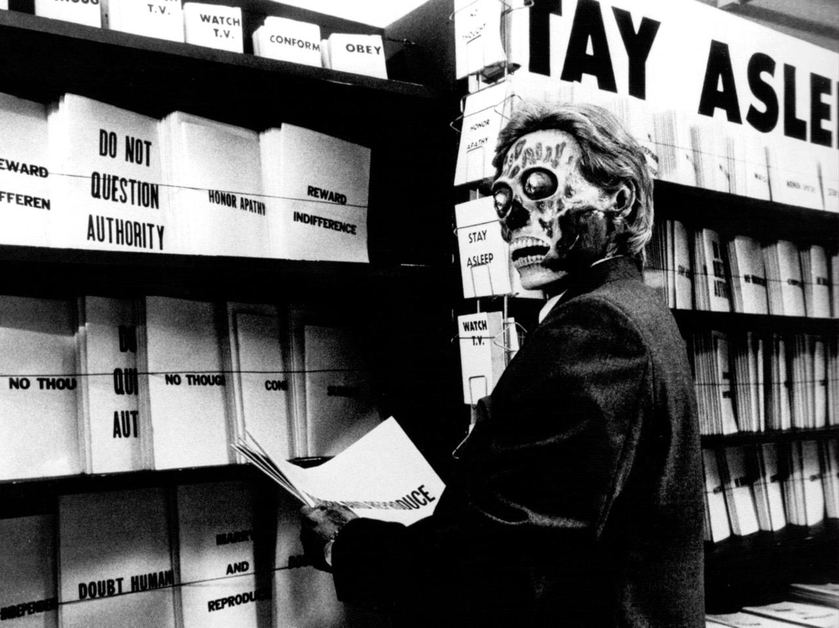

John Carpenter’s They Live, which Carpenter said was a warning about “unrestrained capitalism”. As much as I adore this movie and, in fact, think it is more relevant today than ever, Carpenter does not understand capitalism. What he captures in this dystopian horror is corporatism (the merger between corporation and state), not capitalism (the voluntary exchange of goods and services).

When discussing the prospect of a laissez-faire society, which is to say a society where voluntary exchange is free from interference (regulation, taxation, etc.) from any centralised authority, i.e government, it has long been argued that corporations would engage in the most heinous of activities if not for being restrained by a government (unrestrained capitalism, that is, true capitalism, where capitalism is simply the voluntary exchange of goods and services as described above), and that they would naturally transform into a government themselves in the absence of such a restraint. In reality, it is, in fact, the opposite that is true: corporations can only engage in the most heinous of activities with the aid of a government, and governments are not a natural occurrence that spontaneously manifests itself after an organisation reaches a particular size. Let us dispel this widely held notion by establishing a fundamental understanding of the power dynamic between the seller and the buyer in the marketplace, when government intervention is not possible (because it doesn't exist to intervene).

The seller approaches the buyer with a product they wish the buyer to purchase from them. The buyer will likely have many choices of sellers to purchase this same product from, or a variant of it of a lesser or greater quality, but let us assume the seller is the only one in town offering this particular product. If the seller quotes the buyer an exorbitant price that no buyer is willing to agree to in exchange for their niche product, then no buyer will purchase this product. Thus the seller is forced to lower their price until the buyer is satisfied to commit to the transaction, for if not their business will cease to exist. That's it. Anticlimactic, I know, but in a free market society transactions in the marketplace are that simple. There can be circumstances where a product is of absolute necessity, such as healthcare, and sellers can get away with charging exorbitant prices when they're the only guy in town, but given enough time and dissatisfaction, and given that in such a free market society there are no barriers to entry into the market (because government does not exist to place such barriers via its regulation), competition will always arise to capitalise on that dissatisfaction. Monopoly is therefore impossible to achieve in an unregulated environment, that is, an environment where a government cannot place obstacles in the way of aspiring competitors or outright bar competition from entry into the market.

To circumvent this, a wannabe monopolist could act like a government and stick a gun to people's heads in order to get them to commit to the transaction, but this is unsustainable in such a free market society for two reasons: there are no money trees anymore, and reputation actually matters now; the two factors are inextricably linked. Without a bottomless pit of funds to replenish themselves with, i.e. leveraging government power to give themselves a monopoly, a business is compelled to persuade people to willingly hand over their money. This innately regulates the market, rewarding good behaviour with trust and therefore success, while punishing bad behaviour with scorn and therefore failure, reinforcing reputation as the absolute. Thus it is futile in this environment for a business to choose extortion as their sales tactic, for it is (unsurprisingly) considered a nefarious, immoral action by any decent human being, and the business' reputation will be tainted as such by engaging in it, ultimately leading to their demise.

The retaliation against nefarious business practices will often be simple and peaceful: people will cease to associate with and sustain such an ill-willed business, as they do today. But where there is no legal immunity to hide behind, and where therefore one is held individually responsible for their actions — "I was just following orders" no longer being a viable justification for one's aggression against another — this could escalate when a business goes to great lengths to become a pariah, e.g. engaging in malpractice, extortion, murder. This would most commonly take the form of demands for reparations, i.e. compensation, by those damaged, as is typically the case today when a wrong has been done to oneself by another. These reparations payments would likely be arbitrated by insurance companies, the infrastructure for and practice of which being commonplace in society today already (I refer the reader to The Market for Liberty by Morris and Linda Tannehill for an in-depth study of how private enterprise could trivially resolve the problem of coercion in society in the absence of government). On the other hand, if civility goes by the wayside, violent retribution could be the chosen tool for dispute resolution. However, what one should remember is that reputation applies to the business just as much as it does to the customer, so a tendency to initiate outlandish barbarism to resolve one's conflicts is also innately punished by such a free market society (nobody is in favour of doing dealings with or living next door to an unpredictable brute). In short, in the absence of legal immunity, which is to say protection by government, businesses are entirely at the mercy of the customer and the community, and so they do well to behave accordingly.

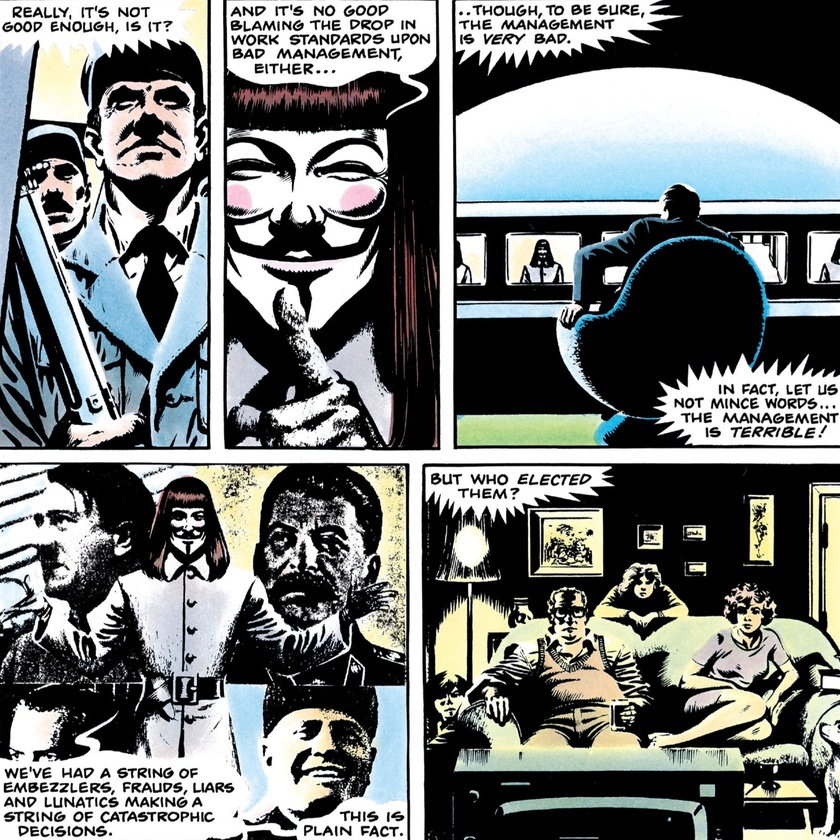

Outside of this free market context however, a business can absolutely get away with such bad behaviour if they pull the right strings and scratch the right backs. In any other context we call this "bribery", but when giving financial incentives to political organisations for privileges we call this "lobbying". This is how and only how monopoly can be achieved. And where there is a lack of choice, businesses tend, much like governments, to increasingly slack on the quality of the service they provide. For they have no financial incentive to do otherwise, with income now guaranteed at the end of the government gun. Competition is the only thing that compels a business to invent, to innovate, to seek better ways to provide value to the customer and, ultimately, persuade them to part with their money, because they can walk away at any moment if left unsatisfied. Without this competition perpetually threatening their existence, they can do exactly what governments do, which is provide no value while reaping all the rewards just the same.

This brings us to PayPal. What they attempted to do by introducing a policy of fining customers $2,500 for what they deem "misinformation" is to become a government, which is to say impose their belief system onto others, coerce people into behaving as they believe they should behave, making the customer beholden to themselves as opposed to themselves being beholden to the customer — a perversion of capitalism. But despite the widely believed notion that corporations spontaneously evolve into a government in the absence of one (not physical but legal absence in this case, with government neither enabling nor disabling PayPal's plans), and that corporations can take over the world whilst nothing can stand in their way, this venture failed instantaneously. For it lacked the two things that allow a government to do what it does with impunity: muscle (to keep people in line) and perception (so people don’t think to get out of line in the first place). Theoretically, PayPal could hire people to abduct its customers, stick guns in their faces, and demand compliance with its new policy. But even if they could muster the muscle to pull this off on such a large scale, without having achieved the latter factor, this would quickly be met with retaliatory force, as well as the mass exodus of its customers (as did happen) and consequently the drying up of PayPal's resources, of which are required to pursue such a quest for world domination in the first place. Being the most popular payment processor in the world, with over 400 million users worldwide, and a net worth of almost $100 billion (at the time of writing), PayPal is most certainly in proportion to the goliath that is the fabled corporate boogeyman dead set on world domination. Yet look how quickly its plans crumbled. Why? Because even if PayPal has the resources, the manpower, and the will, it does not have the perceived legitimacy to do such a thing and for people not to resist them in doing it.

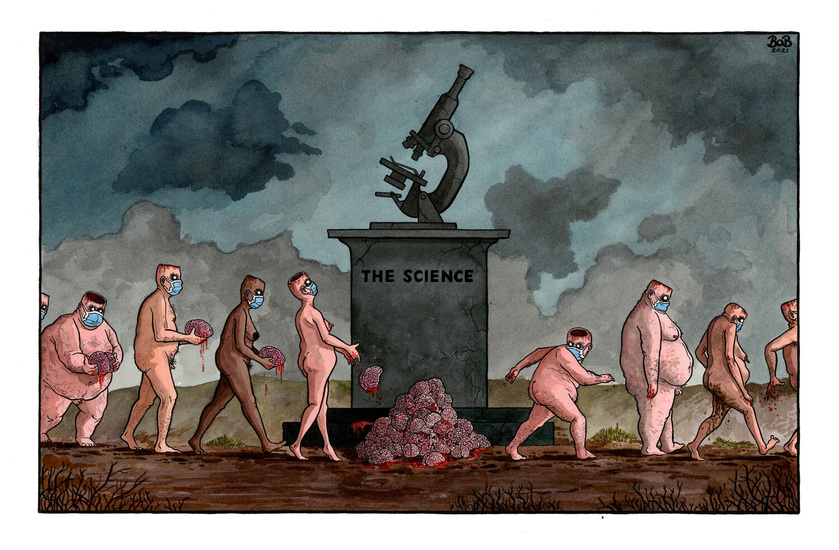

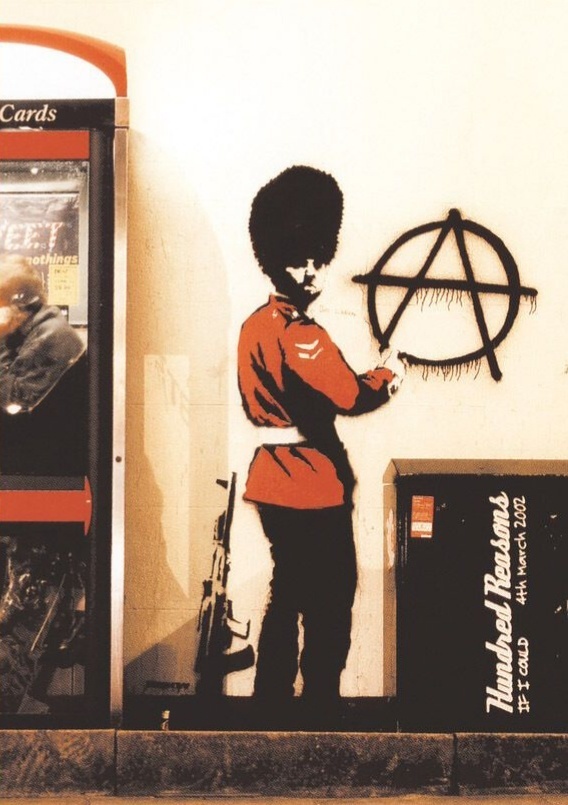

The reason a perception of legitimacy is so crucial is readily apparent, because without it the wannabe ruler would find themselves — due to an overwhelming distaste for their attempts to limit people's lives — in a constant state of turmoil, one which is too great to overcome by brute force, which one lacking such a perception would be left with as their only option, as has always inevitably been the case with oppressive regimes throughout history. The modern day is no different; the same formula applies. If a mugger put a gun to one's head, commanded them to hand over their possessions or face the consequences, no one in their right mind would accept this as a moral act or suggest that one is morally obligated to obey — in fact they would most likely encourage resistance. But if the mugger puts on a costume and calls themselves "the government", despite doing the exact same thing, almost everyone would and, in fact, does accept this as a moral act, and would and, in fact, does insist that one is morally obligated to obey. The difference is plain to see: not that one gang actually possesses the right to rule, but that one has convinced the victim that they possess the right to rule, and consequently that the victim has a duty to obey. Without this, a government would be perceived in the same way any other gang would be, as a gang, the biggest gang in town in fact, and would surely be resisted sooner or later.

This is how PayPal was received in doing what they did because they lacked this perception of virtue: as a gang. But it is not PayPal or any other private entity that is the danger in such a reach for power, for they all are impotent without this perception, no matter their might and determination. It is that which does command such a perception of virtue, and in so doing can get away with such a reach for power, that one should be concerned with: government, the great enabler. If government were to step in and enforce such a policy on PayPal's behalf — much like they did for Pfizer and other pharmaceutical corporations when mandating the consumption of their product during the recent pandemic, and much like they did for GoFundMe when legally backing them to block the Freedom Convoy access to their donations — PayPal could very easily bring about this policy and with it the dystopian future that many wrongly attribute to unrestrained capitalism, i.e. the sort of capitalism where government doesn't get a cut (actual capitalism). On their own and in the absence of such a mafia however, they can bring about nothing.